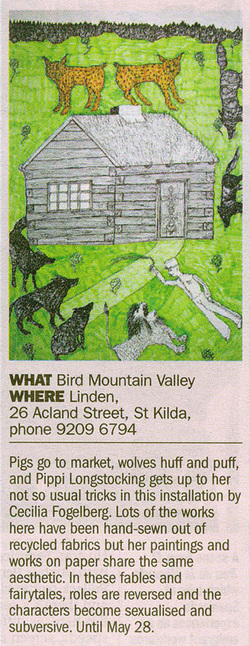

BIRDMOUNTAIN VALLY

Solo show: Linden Gallery, Acland Street, St. Kilda, VIC, 2006

Opening night: Three Wolfmen handing out Vodka Wolf Paws

Exhibition catalogue:

Birdmountain Valley, Linden Gallery, 28 April - 26 May 2006

Birdmountain Valley is a made-up location I first started to visit approximately four years ago. It is to be found between here and nowhere, just behind the mountains. The place grew out of my struggle to find my identity after living in exile from Sweden for several years. I did not feel Swedish and I did not feel Australian; I became a stranger in every position that I took and needed to put words to this struggle. I needed to make a place, an arena, a battlefield for these thoughts of identity battles.

The name Birdmountain refers to my surname Fogelberg; Birdmountain is the direct translation from Swedish into English. I have during my years in Australia considered changing my name to this more suitable English version, not to adapt to suit others, but rather to give my new identity a new name. This has been done before; my surname is originally from Germany, and was adjusted from the German Vogel to the Swedish Fogel (fågel = bird) in the late 1700s. Birdmountain Valley also has references to the old Swedish saying; ‘Bakom berget finns också folk - Behind the mountain other people live´,which simply refers to how people on the other side of the mountain are people as well as we are, and are as wise as we are, irrespective of whether or not we can see them, or know them.

When I had created this metaphorical place, I also realised that I was slowly, but surely building myself a surrounding/home that I could recognise from Sweden; I started to go to IKEA even though I hated IKEA before I left Sweden. I brought from Sweden to Australia strange embroidered kitsch and other ‘typical Swedish’ commodities on my travels, and I started to embrace Swedish traditions that before I had rejected. When my mother visited me for the first time, nearly six years after my arrival in Australia, she was stunned by the level of Swedish kitsch in my home - something that has never occurred in my upbringing. It was then that I understood I played a strong role in the play of cultural and heritage performance.

Once I understood my position, I could also start looking at other people in the same situation - Swedish or not - and I believe it is a phenomenon that happens to most people who choose, or are forced to leave something behind. It happens to emigrants and people in exile, but it is also a performance within one’s culture and the individual’s identity.

Consciously or unconsciously, we are all performing different layers of cultural heritage. Some more than others, for example there is a town in Kansas, US, called Lindsborg - also known as Little Sweden – where people are so strongly playing on their Swedish heritage that the Swedish Dalarhorse* still is the symbol for the city council, and where after 4-5 generations in America, some people still maintain the Swedish language. The welcome note on the Lindsborg’s web page* is still written in Swedish. However, the ‘Swedishness’ in Lindsborg is still very ‘American’, and you’ll find that the heritage is more like the relics of the old country performed in a contemporary way and have therefore become something totally different and unique, drawing from its immediate surrounding.

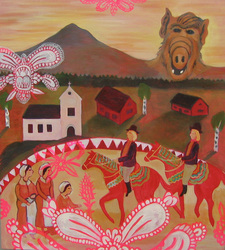

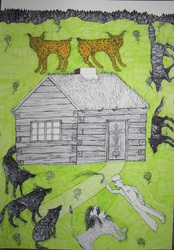

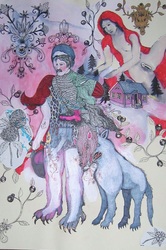

I don’t think that it is necessary for me to draw a parallel between what is happening in Lindsborg to contemporary Australian society, when what I really want to emphasise is not the result, but rather the individual’s action. Birdmountain Valley is not a Lindsborg. Birdmountain Valley is instead the virtual framework where the battle of the individual’s identity is fought and where the different colours of the individual’s cultural make-up are applied. It is a place where cultural icons, contemporary mythological heroes and gender issues are questioned and penetrated. It contains the deep forests of story telling and modern fairy tails - where most often the roles of the characters have been swapped - and where the pray has killed its hunter and no one is walking safely. It is like an adult Pipi Longstocking’s Viller Villerkulla* where one creates one’s own realities and rules and where the context of the language is made up as we walk through.

The Birdmountain Valley is a place where nothing is taken for granted and where you are always questioned about your origin. When I ended up in the emergency ward at St Vincent’s Hospital just a few weeks ago, the first question the nurse asked me was: -At which backpackers are you staying?- And I said:-At the one on the right hand side, just in front of the deep forest, on the left of the river, in Birdmountain Valley.-

Cecilia Fogelberg, 2006

Languages are our mirrors: they can bring into focus their own angle on reality and the universe surrounding us. The acquisition of new language opens up a new canvas onto which the world can take shape, and at the same time it enhances the portrait painted with one's mother tongue by drawing parallels and forming contrasts between the two (or more) languages.An old Czech saying states: 'learn a new language and get a new soul'.

*1 A red hand painted wooden horse from Dalarna, still used as a national symbol for Sweden

*2 http://www.lindsborgcity.org/

*3 Astrid Lindgren’s famous children's book character Pipi Longstocking’s house; Viller Villerkulla.

Birdmountain Valley is a made-up location I first started to visit approximately four years ago. It is to be found between here and nowhere, just behind the mountains. The place grew out of my struggle to find my identity after living in exile from Sweden for several years. I did not feel Swedish and I did not feel Australian; I became a stranger in every position that I took and needed to put words to this struggle. I needed to make a place, an arena, a battlefield for these thoughts of identity battles.

The name Birdmountain refers to my surname Fogelberg; Birdmountain is the direct translation from Swedish into English. I have during my years in Australia considered changing my name to this more suitable English version, not to adapt to suit others, but rather to give my new identity a new name. This has been done before; my surname is originally from Germany, and was adjusted from the German Vogel to the Swedish Fogel (fågel = bird) in the late 1700s. Birdmountain Valley also has references to the old Swedish saying; ‘Bakom berget finns också folk - Behind the mountain other people live´,which simply refers to how people on the other side of the mountain are people as well as we are, and are as wise as we are, irrespective of whether or not we can see them, or know them.

When I had created this metaphorical place, I also realised that I was slowly, but surely building myself a surrounding/home that I could recognise from Sweden; I started to go to IKEA even though I hated IKEA before I left Sweden. I brought from Sweden to Australia strange embroidered kitsch and other ‘typical Swedish’ commodities on my travels, and I started to embrace Swedish traditions that before I had rejected. When my mother visited me for the first time, nearly six years after my arrival in Australia, she was stunned by the level of Swedish kitsch in my home - something that has never occurred in my upbringing. It was then that I understood I played a strong role in the play of cultural and heritage performance.

Once I understood my position, I could also start looking at other people in the same situation - Swedish or not - and I believe it is a phenomenon that happens to most people who choose, or are forced to leave something behind. It happens to emigrants and people in exile, but it is also a performance within one’s culture and the individual’s identity.

Consciously or unconsciously, we are all performing different layers of cultural heritage. Some more than others, for example there is a town in Kansas, US, called Lindsborg - also known as Little Sweden – where people are so strongly playing on their Swedish heritage that the Swedish Dalarhorse* still is the symbol for the city council, and where after 4-5 generations in America, some people still maintain the Swedish language. The welcome note on the Lindsborg’s web page* is still written in Swedish. However, the ‘Swedishness’ in Lindsborg is still very ‘American’, and you’ll find that the heritage is more like the relics of the old country performed in a contemporary way and have therefore become something totally different and unique, drawing from its immediate surrounding.

I don’t think that it is necessary for me to draw a parallel between what is happening in Lindsborg to contemporary Australian society, when what I really want to emphasise is not the result, but rather the individual’s action. Birdmountain Valley is not a Lindsborg. Birdmountain Valley is instead the virtual framework where the battle of the individual’s identity is fought and where the different colours of the individual’s cultural make-up are applied. It is a place where cultural icons, contemporary mythological heroes and gender issues are questioned and penetrated. It contains the deep forests of story telling and modern fairy tails - where most often the roles of the characters have been swapped - and where the pray has killed its hunter and no one is walking safely. It is like an adult Pipi Longstocking’s Viller Villerkulla* where one creates one’s own realities and rules and where the context of the language is made up as we walk through.

The Birdmountain Valley is a place where nothing is taken for granted and where you are always questioned about your origin. When I ended up in the emergency ward at St Vincent’s Hospital just a few weeks ago, the first question the nurse asked me was: -At which backpackers are you staying?- And I said:-At the one on the right hand side, just in front of the deep forest, on the left of the river, in Birdmountain Valley.-

Cecilia Fogelberg, 2006

Languages are our mirrors: they can bring into focus their own angle on reality and the universe surrounding us. The acquisition of new language opens up a new canvas onto which the world can take shape, and at the same time it enhances the portrait painted with one's mother tongue by drawing parallels and forming contrasts between the two (or more) languages.An old Czech saying states: 'learn a new language and get a new soul'.

*1 A red hand painted wooden horse from Dalarna, still used as a national symbol for Sweden

*2 http://www.lindsborgcity.org/

*3 Astrid Lindgren’s famous children's book character Pipi Longstocking’s house; Viller Villerkulla.